Sydney artist Martin Sharp created one of the most enduring images of the 60s with an Oz cover featuring two naked, flower-strewn twins. But what happened to them as the bleaker winds of the 80s and 90s started blowing?

By Mick Brown

One fine summers day in 1967, Martin Sharp, the art editor of Oz, the underground magazine, collected a photographer and two models, the 17year old Aloszko twins, Michelle and Nicole, and set off into the Surrey Countryside to add a little footnote to history.

They found a suitably secluded and Arcadian setting and refreshments were served. Michelle and Nicole then took off their clothes, garlanded themselves with flowers bought from a florist en route, and frolicked for the photographer, Bob Whitaker. It was the summer of love after all, and people did things like that.

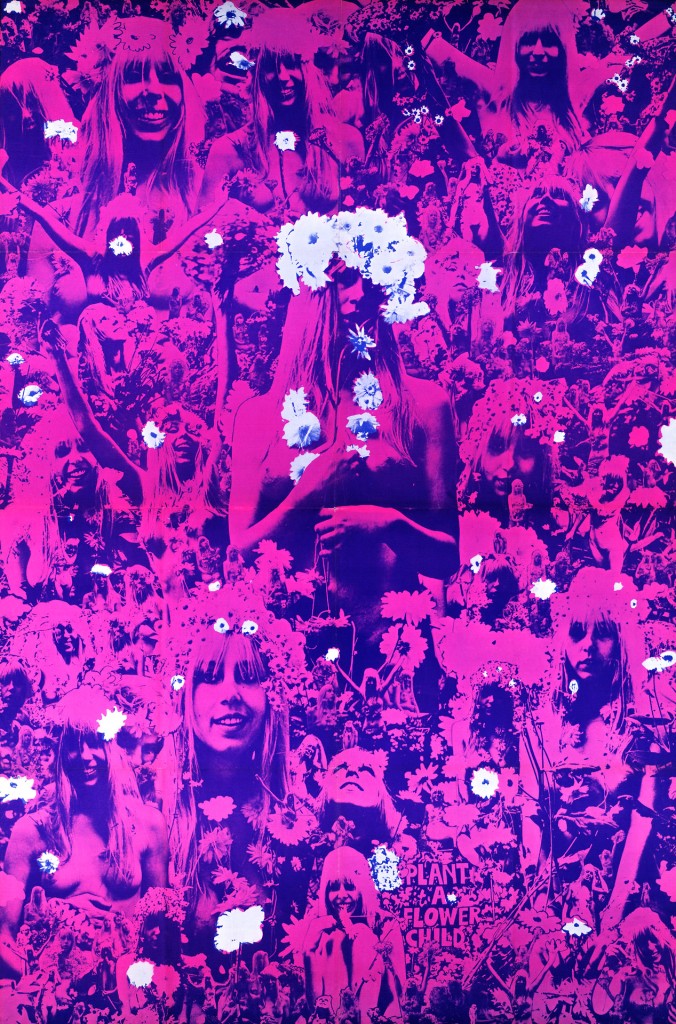

A month later, the fruits of the afternoon in the country were revealed to the world (an so were the Aloszko twins) in the form of a special Oz issue with the magazine printed on the back of a Day-glo pink and blue poster showing the twins playing peek-a-boo with their floral arrangements, the very picture of sweet, heady, virginal, hippie innocence.

“It was a period of optimism,” says Martin Sharp, “and we wanted to produce a poster that reflected the spirit of the times.” It was also, he adds, “a cheap way of producing the magazine.” Retailing for 2s 6d, the poster, with its epigrammatic exhortation to “plant a flower child”, sold in its tens of thousands and in the process became one of the defining images of the sybaritic, silly 60s.

Indeed in Hippie Hippie Shake, Richard Neville’s new account of the times, one of the key scenes happens in the presence of the twins – with Martin Sharp brewing up some special tea for Neville with the result that the twins, giggling and naked, appeared to become quads, then sextuplets.

Certainly sales of the poster saved Oz, which had been floundering on the brink of bankruptcy, and, for a time at least, everything in the garden was lovely. The magazine survived for another three years before it closed following the notorious trial of its editors on obscenity charges. The hippie dream evaporated. Oz readers who had pinned the poster to their walls went on to become lawyers, police inspectors and trust hospital managers. Those mindful enough of posterity to have kept their poster in a safe place can now expect to sell it for about £500 at a London auction house.

And the Aloszko twins. What happened to them?

Tall and long-legged, with their Jean Shrimpton-meets-Joni Mitchell cornfields curtains of hair, at the age of 45 the twins still carry a breath of the 60s about them. Michelle lives in West London; Nicole in Canada. They have seen each other only twice in the past 20 years. Yet according to Michelle, throughout their lives have remained, “each others best friend. Its as if we know each others thoughts”. They dress alike, share the same tastes in books, music, food, “everything except men”. They even have the same number of children – four – although their paths through life have been very different.

As children, the Aloszkos were always inseparable. Their father was a tailor from Ukraine who abandoned their mother before they were born. They grew up in a council flat in North London – twins, mother and grandmother.

In many ways the Aloszkos followed a path that typified the popular image of the sixties. From school, they graduated straight to sales assistants at Biba, less a boutique than a sixties idea of nirvana. Kohl-eyed and dressed in crushed velvet, they danced at the Speakeasy club, and then became models. Their first assignment was for a television and poster campaign, launching London’s new Sun newspaper. They became known as “The Sun Twins”. They were just 16.

The Oz poster was hardly a proper commission at all. It was a lark. Michelle’s first thought was “to hope my mother didn’t see it”. They were paid £12 10s each; after it was published, their agent spread the poster out on her office floor, counted the multiple images and declared they had been “ripped off”.

“Martin and Bob saw us as the definitive flower children,” says Nicole. “But we were never real hippies. I think we were too free-spirited for that”.

However, the Oz poster made them mini-stars of the 60s scene.

They dined with Yul Brynner at the Savoy, and with Paul Kantner of Jefferson Airplane; they went to Roman Polanski’s party and resisted his invitation to take off their clothes. When they bolted the for the door, Polanski chased them around Sloane Square until they made good their escape in a taxi.

“Richard Donner, the film director, invited us over to his apartment in Chelsea, and said he wanted to do some filming,” remembers Nicole. “He said, ‘what would you do on a rainy day when you’ve got nothing else to do, and your at home together…’

“He had this lovely library, so we sat there talking, then picked a book out each and started reading, while he sat there with his camera in his hand, getting more and more uptight. He had something different in mind.

In 1968, the twins went to Paris where they worked as models. The students were in revolt on the City streets: the Aloszko twins dined with Salvador Dali and with Bernie Coldfield.

They made good money, and spent every penny of it. They led, in short, charmed lives.

As the 60s gave way to the 70s, Michelle moved to Amsterdam, living with a “wheeler-dealer” who dealt in “soft drugs, cars, whatever”. One day she got on a train to Amsterdam, bound for the South of France, carrying a slab of hashish wrapped in brown paper. A man met her at the station in Nice, and they drove to the house of Keith Richard of the Rolling Stones, who seemed particularly pleased to see her.

She returned to London and met “a drifter” by who she had her first child Tanith, in 1971. She supported herself by working in clothes shops and book stores.

In London, Michelle met a schoolteacher and in 1977 gave birth to her second child, Jake. They settled in the country, but that relationship did not work out either, and she returned to London a single mother once more.

While Michelle acknowledges that she spent a large part of the 70s “just floating around”, Nicole found her anchor much sooner.

After living and working in Paris with her sister, Nicole, too, left on the hippie trail, first to Morocco, then on to Denmark, and finally to Canada. There, in 1973, she met Gary, a logger, who was to become her husband. She returned to England, but found herself pining for Canada and when Gary proposed, she accepted. They have now been married for 20 years and have four children between four and 17.

“It was a marriage of convenience to start with,” says Nicole, “but then I realised I was falling in Love with him.”

Michelle, twice and unmarried mother, acknowledges her life could seem rootless.”Bur I think I’ve been incredibly lucky in what I’ve experienced. The 60s was a wonderful era and I feel lucky we came through it unscathed”.

The early 80s found Michelle back in London, the mother of two growing children, casting around for something to do with her life. She enrolled in a sociology course where she fell in love with her tutor, John. She was already pregnant with her third child, Jack, when they married in 1985. Their second son, Zachary, was born in 1988.

For the past nine years Michelle has worked as the manager of a London bookshop. She says: “Of the two of us, I think I’ve ended up with more stability, which is ironic”.

Ask Nicole if she is happy and she replies that yes, she is, “although I sometimes feel theres something missing”.

She looks back on her afternoon in the Surrey countryside, and the Oz Poster, with a particular fondness, “because it’s lasted” – a small fragment of a more optimistic age.

“Mish and I were able to drift because we were the marketable product. One thing would just lead to another. My kids will never have the same sense of freedom”.

And if her own 17-year-old daughter was offered the chance to drive into the countryside and plant a flower child poster?

I wouldn’t have any qualms,” says Nicole. “In fact, I would probably want to be in on it. But one good thing I’d make sure is that she got paid for it”.